Introduction and Index

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

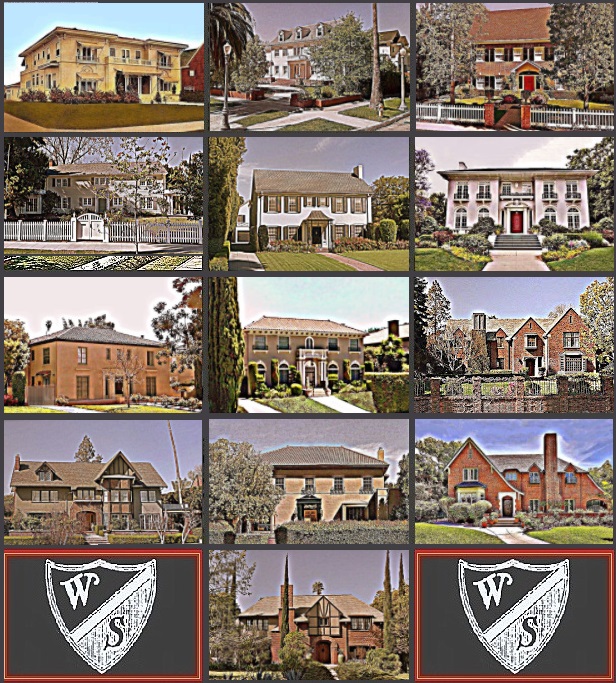

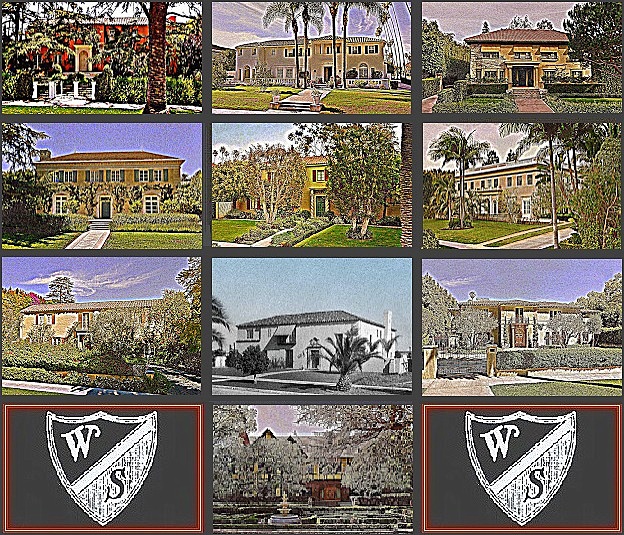

OWING TO THE PROMINENCE OF ITS NAMESAKE family as well as to its being a decade newer than the adjacent but distinct subdivisions of Fremont Place and Windsor Square, the Hancock Park neighborhood of Los Angeles has gained the upper hand in terms of name recognition in the larger district. More often than not, real estate listings referring to houses within the borders of, for example, our subject, Windsor Square—the first phase of which opened in 1911—describe them as being in Hancock Park. Some homeowners in the more venerable Square seem not to mind the subsumption of their own historic neighborhood. Other residents, understanding the particular urbanity of early Windsor Square's rectilinear boulevards as opposed to the curving suburban roadways of the actual Hancock Park (as well as of gated Fremont Place just south across Wilshire and a fifth Windsor Square tract north of Third Street), prefer to maintain a distinction. It is with this preference in mind that we have cataloged here the houses—original, demolished, and newer, as well as the surprising number relocated from other districts—along the four blocks each of Irving, Lorraine, Windsor, Plymouth, Lucerne, and Arden boulevards south of Third. These streets compose an actual near-square bordered by Wilshire Boulevard on the south, Third Street on the north, and the area between a half-block west of Arden and a half-block east of Irving boulevards comprised of the three original tracts of Windsor Square.

|

The Mountbattens had yet to change their name, but Windsor Castle had long been a famous landmark when the earliest Windsor Square real estate syndicate was incorporated in 1892; once platted in 1911, the names of some streets in the new subdivision enhanced the English air of its "park-like setting." Windsor and Plymouth boulevards are obvious. While "Arden" may have been suggested by D. W. Griffith's popular 1911 film adaptation of Tennyson's narrative poem "Enoch Arden," it has also been suggested that the name—and that of Lucerne Boulevard—were taken from local dairies. Lorraine was named for developer Robert Rowan's daughter; Irving is said to have been named in exchange for the purchase of several seed lots by 1911 syndicate partner Irving Hellman. The ad below appeared in the Los Angeles Express on July 5, 1911. |

The composite of plates from the 1921 edition of Baist's Real Estate Atlas seen above on this page illustrates the three earliest developmental phases that compose Windsor Square. Lots in the mother, "Windsor Square Tract 1390," went on sale in 1911 after being surveyed that July and officially recorded on September 21. Sales in the Wilshire Heights addition, Tract 1476, and in Tract 2136 to its north, began two years later. Not included in our current survey but extending north from Third Street to Beverly Boulevard (originally designated Temple Street), Tract 3501, promoted as Windsor Heights, included the area with longitudinal borders a half-block west of Arden Boulevard (originally Vine Street) and the west curb of Larchmont Boulevard; in between Arden and Larchmont is the northward extension of Lucerne Boulevard, originally designated El Centro Avenue.

|

| While the various tracts laid out on the original 200 acres bought by the 1911 syndicate behind the Windsor Square Investment Company were marketed separately with different names, all were eventually considered one. The unified Windsor Square struggles to maintain its own identity in the face of the preference of many for it to be considered part of Hancock Park, officially an entirely separate subdivision just west. On this 1921 Baist real estate map, north is to the right; Vine Street is now Arden Boulevard, El Centro Avenue is Lucerne Boulevard, and Temple Street became Beverly Boulevard. |

After the uncertainties of the First World War, the final phase of Windsor Square, tract 3743—again not part of our current survey—was formally offered by a third team of developers, F. H. Woodruff, Tracy E. Shoults, and Frank Meline, in May 1920. Promoted as "New Windsor Square" and composed of somewhat smaller lots for homeseekers of somewhat smaller means than those targeted in the earlier offerings before the war, New Windsor Square largely eschewed the original stately geometry of Windsor Square in favor of curving drives, which apparently by the 1920s had come to be be seen as more impressive than rectilinear roadways; in this way New Windsor Square became, in essence, a poor man's Hancock Park or Fremont Place. Today, all of Windsor Square is luxurious, if not in the manner of the Westside suburbs that would usurp if not eclipse all central Los Angeles subdivisions of the 1910s and early '20s. While, for example, the grandeur, privacy, and scale of Bel-Air—developed on the heels of Windsor Square and Hancock Park—would cast the slightly older developments in a more upper-middle-class light, it would not render them wholly unfashionable as they had in turn the languishing larger West Adams district, which began a sad 30-year decline just as Park Mile–adjacent neighborhoods and those farther west captured the imagination of affluent Angelenos by the mid '20s. (More on New Windsor Square is at The Homestead Blog, a seriously invaluable Southern California history resource accessible here.)

While some sources cite the date of its founding as seven years earlier, the Los Angeles Herald of March 18, 1892, reported that "The articles of incorporation for the Windsor Square Land company were placed on file in the county clerk's office yesterday.... The board of directors is composed of Maurice S. Hellman, Joseph Kurtz, H. Boettcher, A. W. Eames and M. D. Johnson." While the earlier date would have coincided with the great railroad-driven Southern California boom of the '80s, within a year of the 1892 date of the founding of Windsor Square the United States economy found itself on the threshold one of the worst depressions in its history. Windsor Square would remain so much acreage of amber waves of grain—and barley and beans—for nearly 20 years until its progenitors deemed the economy not only recovered but advanced to the point where a magnificent return could be realized. Reports vary as to the killing made by Maurice S. Hellman and his partners in 1911, when, on June 2, the 200-acre spread—said to have been acquired by John C. Plummer in the 1860s for $1.25 an acre and by the original interested parties in 1892 for $4.00—cost its new set of investors $5,000 an acre. According to the Los Angeles Times of June 3, 1911, the $1,000,000 transaction was "the largest deal in inside acreage in the history of Los Angeles." The name of the new entity was a slight variation on that of the 1892 organization; the property now officially belonged to the Windsor Square Investment Company.

|

| A northerly view over Windsor Square, circa 1918. The Marlborough School had moved to the northeast corner of West Third and the future Rossmore Avenue from West Adams in 1916; not yet platted is New Windsor Square, which would open in 1920. The north-south row of trees between Plymouth and Lucerne marks the west boundary of the first tract, opened in 1911. The eastern boundary of the current greater Windsor Square neighborhood now seems to vary, with some real estate interests claiming Wilton Place while, less dubiously, serious preservationists stop at a half-block east of Van Ness Avenue. |

The new syndicate of developers, spearheaded by prominent real estate promoter Robert A. Rowan and including several relatives of 1892 principal Maurice S. Hellman, had no plans to sit back for another 20 years even if their unimproved acquisition lay at the far reaches of Los Angeles. The property, within new city limits established with the annexation of Hollywood among other towns by 1910 but still far out along dusty Wilshire Boulevard, was in what soon came to be referred to as the "West End" of the city. Residential development of the Wilshire District, extending in a broad corridor north and south of the boulevard, was exploding. Newly motorized, affluent Angelenos were seeking more commodious lots and newer housing than had been the norm in the older fashionable districts southwest of downtown toward U.S.C. whose designs had been determined by streetcars and buggies. Although West Adams had been gaining expensive new neighborhoods in its western reaches such as Berkeley Square and Lafayette Square—both of which tried competing directly with new Wilshire development—the tide was distinctly to the northwest. Rowan and his partners described their intentions for Windsor Square to become "a second Chester Place on a much more magnificent scale." While that gated 13-year-old subdivision toward the east end of West Adams was indeed well-known, it was more of a symbol of affluence than a welcoming one, dominated as it had quickly come to be by newly rich former telephone operator Estelle Doheny. While some listed in the Southwest Blue Book—Los Angeles's answer to the New York–based Social Register—held firm in West Adams, some even for decades as it fell about their ears, most of the bon ton and professional classes looked to the future in the transforming beanfields out on Wilshire Boulevard.

The original namesake Windsor Square tract, numerically designated Tract 1390 on real estate maps, would prove to be the showpiece, the one with all the trimmings. The four boulevards from Irving west would be paved in concrete—most of which is in place today—while later tracts, developed by various concerns piggybacking on the original's reputation for luxurious features, made do with asphalt. (The official border of tracts 1390 and 1476, for example, are made clear by the abrupt change in the surfaces of Fourth and Fifth streets between Plymouth and Lucerne boulevards, concrete to the east, asphalt to the west, which indicated that different developers laid out the streets.) Tract 1390 also received superior lighting in the form of metal standards with plaques on their bases embossed "WS" and topped originally by three French-inspired Alba-glass fixtures. It is unclear as to whether all four boulevards of Tract 1390 received the triple lamps or whether some, although using the same "WS" standards, were topped with the round globes that were the forerunners in Windsor Square of today's urn- or acorn-shaped style practically synonymous with Los Angeles through film and television. At any rate, lighting standards in the later tracts of the Square were from the beginning uninitialed concrete topped by single fixtures.

While streets in some older grand neighborhoods of Los Angeles had the luxury of having their utilities mostly out of sight on poles in back service alleys, some blocks of Windsor Square, along with parts of its competitor across Wilshire, Fremont Place—also opened in 1911—were reportedly the first in the city with all wiring buried underground; modern suburbia was in this way born. Other deed stipulations reported in early hype for Tract 1390 were minimum 100-foot frontages, 40-foot setbacks, 20-foot "parkings" (parkways, which in Los Angeles refers to the landscaped area between curb and sidewalk), and that a remarkable $30,000 must be spent on construction by homebuilders—more than $700,000 in 2016 dollars. Curiously, though, the minimum figure cited in advertisements appearing in newspapers during 1914, after the initial hype, made an appeal to "people of moderate means" and cited $10,000 as the minimum. Perhaps the market was slowing down. The budget for Tract 1390's roadways, utilities, and landscaping was reported to be $200,000.

While streets in some older grand neighborhoods of Los Angeles had the luxury of having their utilities mostly out of sight on poles in back service alleys, some blocks of Windsor Square, along with parts of its competitor across Wilshire, Fremont Place—also opened in 1911—were reportedly the first in the city with all wiring buried underground; modern suburbia was in this way born. Other deed stipulations reported in early hype for Tract 1390 were minimum 100-foot frontages, 40-foot setbacks, 20-foot "parkings" (parkways, which in Los Angeles refers to the landscaped area between curb and sidewalk), and that a remarkable $30,000 must be spent on construction by homebuilders—more than $700,000 in 2016 dollars. Curiously, though, the minimum figure cited in advertisements appearing in newspapers during 1914, after the initial hype, made an appeal to "people of moderate means" and cited $10,000 as the minimum. Perhaps the market was slowing down. The budget for Tract 1390's roadways, utilities, and landscaping was reported to be $200,000.

|

| Suffering a degree of deferred maintenance in the uncertain 1970s as was a good bit of Windsor Square's housing stock, stalwart residents began to appreciate the historic and aesthetic value at hand in the '80s. When the city revealed plans to modernize lighting in the original tract to address concerns about crime, what are called "Windsor Square Specials" became the objects of serious affection and lumen upgrades instead. On November 22, 1988, the Los Angeles City Council voted to authorize a lighting preservation ordinance for Windsor Square, the first of its kind in the city. |

As with almost every other new subdivision developed along the Wilshire corridor from Westlake (MacArthur) Park, Windsor Square was described on its incorporation day by the Times as "high and sightly, commanding an unsurpassed view of the mountains, the ocean front, and the rest of the city"...that is, at least, until trees, buildings, and smog intervened, none of which dazzled visitors to tract offices could, of course, foresee. In the early promotion of the Square, lots were laid out to vary from 100 to 300 feet wide—"there will be no small lots." All water and gas lines, sewers, and electrical conduits were to be run to the rear of houses in order to eliminate the necessity of tearing up the streets in making repairs or additional improvements. Just as the promotional names of its separate tracts were before long dropped in favor of that of the more prestigious original, so too over the years did it seem that yet another ambitious new development next door would take over the identity of Windsor Square entirely. Characterized by curving drives and concrete streets, Hancock Park began to be promoted in earnest during 1921 as "a subdivision representative of the integrity behind the growth of Los Angeles." Its success and later edge in prestige over Windsor Square owed no doubt to the currency of the Hancock name in the city. G. Allan Hancock had given the county the 23 acres of open space of the now confusingly named Hancock Park to the west; all part of his inherited childhood stomping grounds, the eastern section of his branch of the Hancock family's 2,400 acres of the old Ranch La Brea would be developed for profit. Allan Hancock's mother, the indomitable Ida, had earlier bet on the residential primacy of Wilshire Boulevard, completing the extravagant "Villa Madama" at the northeast corner of Vermont Avenue in 1910. Such was the growth of Los Angeles that barely a decade later, the never successful idea of Wilshire Boulevard as a linear neighborhood of palaces began to be abandoned. Development in the new West End was the ticket, putting an end to Gaylord Wilshire's domestic dream and effectively signing the death warrant of the West Adams district.

|

| Elaborate display advertisements for Windsor Square ran in the Times and the Herald during its first few years. Remarkable is that so many affluent homebuilders were willing to put up with years of sparse vegetation until the carefully designed landscaping matured. In the example at left, which appeared in the Herald on April 5, 1913, the house that still stands at 419 Lorraine Boulevard, one of the first built, is seen soon after completion. |

It could be that even some homeowners east of Rossmore think they are living in Hancock Park, or prefer to let others think they do—just as those in adjacent, less ambitious tracts enjoyed the limelight of Windsor Square in its first decade, before Hancock Park emerged. As decades passed, all of the Park Mile neighborhoods—dominated by the three grandest, Hancock Park, Windsor Square, and Fremont Place—managed to hang on to their varying degrees of esteem despite competition from newer, much more expensive developments from Beverly Hills west. Even as the city began to reel in the mid-1960s under ever smoggier skies, gut-punched by the Watts Rebellion in August 1965 and the Tate-LaBianca murders four years later—all exponentially accelerating white flight from central Los Angeles, stoking alarm and alarm installations—Windsor Square and its neighbors held relatively firm. It first appeared that, as the value of its aging, money-pit housing stock sagged, the neighborhood was destined to go the way of once-similar ones to the east beyond Irving. By the early '70s, as an eyewitness described his point of view, the constant fear and threat of the white-flight-ravaged neighborhoods to the east took its toll on the devotion to the district "of big Catholic families and Old Guard money whose uniformed maids shopped along Larchmont Boulevard." As had J. Paul Getty in the mid '50s, developers in the '70s pushed to rezone Wilshire Boulevard in the district, from Olympic to Sixth—including a plan to purchase and demolish the entirety of Fremont Place—for high-rise office construction in order to create something of a "mini–Century City," as one observer noted. Somehow, after beginning to recover in the '80s, equilibrium returned. The Westside was built out and, farther from the dystopian inner city, that much more expensive to move to. While many descendants of originals stood fast, a new guard, respectful of them and eyeing the potential and undeniable charm and craftsmanship of Windsor Square, worked hard to bring back the 1911 vision of Robert Rowan and his partners. While this may have involved giving into the superior currency of the Hancock name, the authors believe that, while there may be more noble pursuits in the world, Windsor Square must regain its own identity. It is to this minor civic wish that this inventory of the first three tracts of what its developers called "The Residential Masterpiece" is dedicated.

PLEASE ALSO SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES:

INDEX

PLEASE NOTE THAT THE ABBREVIATION "BP" USED

THROUGHOUT OUR INVENTORY REFERS TO THE BUILDING

PERMITS ISSUED BY THE LOS ANGELES DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING

AND SAFETY AND ITS PREDECESSORS, THE DEPARTMENT OF

BUILDINGS AND THE SUPERINTENDENT OF BUILDINGS

South Irving Boulevard

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 300 BLOCK OF SOUTH IRVING BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

301 302 310 311 320 321 323

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 400 BLOCK OF SOUTH IRVING BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

404 405 414 415 424 425

434 435 444 445 454 455

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 600 BLOCK OF SOUTH IRVING BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

604 605 610 617 620

627 628 638 641

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 500 BLOCK OF SOUTH IRVING BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

532 533 541 542 554 555604 605 610 617 620

627 628 638 641

Lorraine Boulevard

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 300 BLOCK OF LORRAINE BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

301 304 315 316 321 322

327 332 337 340 356 357

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 400 BLOCK OF LORRAINE BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

404 414 419 420 425 426

434 435 444 454 455

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 500 BLOCK OF LORRAINE BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

500 505 515 524 525 532

South Windsor Boulevard

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 300 BLOCK OF SOUTH WINDSOR BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

301 304 315 317 322 326

330 333 343 354 355

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 400 BLOCK OF SOUTH WINDSOR BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

400 401 414 415 424 425

434 435 444 445 454 455

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 500 BLOCK OF SOUTH WINDSOR BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

502 505 514 515 524

531 532 542 550 553

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 600 BLOCK OF SOUTH WINDSOR BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

601 606 616 617 626 627 637

South Plymouth Boulevard

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 300 BLOCK OF SOUTH PLYMOUTH BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

303 304 309 314 315 322 325

332 333 340 343 354 355

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 400 BLOCK OF SOUTH PLYMOUTH BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

400 403 420 424 425 434 435

441 444 447 449 455 456

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 500 BLOCK OF SOUTH PLYMOUTH BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

501 504 523 528 535

538 545 546 552

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 600 BLOCK OF SOUTH PLYMOUTH BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

605 606 617 626 627 636

South Lucerne Boulevard

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 300 BLOCK OF SOUTH LUCERNE BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

300 301 310 311 316 317 322 325

332 333 340 345 346 347 354 355

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 400 BLOCK OF SOUTH LUCERNE BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

400 401 409 410 417 418 426427 432 433 440 441 450 459

501 504 510 511 518 523 520

527 532 533 540 541 549 550

602 605 606 617 618

629 630 637 638

South Arden Boulevard

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 300 BLOCK OF SOUTH ARDEN BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

300 301 310 311 316 317 322 325

332 333 340 341 347 348 353 354

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 400 BLOCK OF SOUTH ARDEN BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

400 401 410 411 418 419 426 427

432 433 440 441 448 449 456 457

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 500 BLOCK OF SOUTH ARDEN BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

500 505 510 511 518 519 526

527 532 533 540 541 549 550

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 600 BLOCK OF SOUTH ARDEN BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

601 604 606 615 616 623

624 631 632 639 640 645

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE 300 BLOCK OF SOUTH ARDEN BOULEVARD, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

300 301 310 311 316 317 322 325

332 333 340 341 347 348 353 354

400 401 410 411 418 419 426 427

432 433 440 441 448 449 456 457

500 505 510 511 518 519 526

527 532 533 540 541 549 550

601 604 606 615 616 623

624 631 632 639 640 645

Side Streets

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE SIDE STREETS OF WINDSOR SQUARE, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

4665 West Fourth Street

4857 West Fourth Street

4763 West Fifth Street

4518 West Sixth Street

4521 West Sixth Street

4618 West Sixth Street

4619 West Sixth Street

4664 West Sixth Street

FOR DETAILS ON THE HOUSES OF THE SIDE STREETS OF WINDSOR SQUARE, CLICK ON ANY ADDRESS BELOW

4665 West Fourth Street

4857 West Fourth Street

4763 West Fifth Street

4518 West Sixth Street

4521 West Sixth Street

4618 West Sixth Street

4619 West Sixth Street

4664 West Sixth Street

Illustrations: HDL; The David Rumsey Map Collection; USCDL; LAH; LAE; SB/NHM;

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps; Private Collections